Pristina, Kosovo: A New Country, Bill Clinton, 2 Jews (including an Omahan), and Albanian Muslims

Alexander Hamilton, the Broadway Hit, and the Jewish Connection

January 3, 2020

Mali: Fran versus the Diviner of the Desert

January 3, 2020Pristina, Kosovo: A New Country, Bill Clinton, 2 Jews (including an Omahan), and Albanian Muslims (2014)

By Rich Juro

Why did we decide to journey to the little country of Kosovo and its capital city, Pristina? We were on the way to Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia and Herzogovinia, to join a World War I tour, and Kosovo is a new country right “in the neighborhood”. So Fran and I flew in for a brief but interesting visit. Here’s the story:

Kosovo Map in Balkans During Ind. War

Pristina (pronounced Prish-teen-ah) is a city of 500,000 that is the capital of Kosovo. A landlocked country in the Balkans of Southeastern Europe, Kosovo was formerly a province of Serbia, which itself was part of Yugoslavia. The Kingdom of Yugoslavia was created when the old Austro-Hungarian Empire collapsed at the end of World War I. Many people remember Marshal Tito, the maverick Communist who led Yugoslavia for 35 years after World War II. But after he died in 1980, Yugoslavia began to fall apart. There were religious and ethnic wars. The tragic results were not just military battles but civilian atrocities, and even an ethnic-cleansing genocide. 6 autonomous republics — Slovenia, Croatia, Macedonia, Serbia, Montenegro, and Bosnia and Herzegovina — became separate nations.

Kosovo, still a province of Serbia in 1991, voted overwhelmingly in favor of an independence referendum. The movement for independence gradually escalated from non-violent protests to aggressive encounters, which prompted an increasingly fierce Serbian military response. President Bill Clinton had American and NATO planes bomb the Serbs in 1999. The Serbs withdrew, and a United Nations transitional administration was instituted. In 2008, Kosovo declared itself an independent country that is now recognized by 107 nations. It has not been admitted to the UN, probably because UN Security Council members Russia and China do not like ethnic and religious minorities declaring their independence. Russia also has ancient ties with Serbia: both countries are primarily Slavic peoples of the Christian Orthodox religion, while most people in Kosovo are Muslim. Ironically, another international commission is now looking into whether the Kosovars themselves committed war crimes against local Serbs or Roma (gypsies).

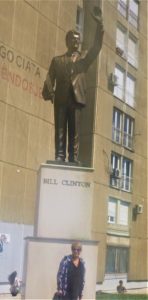

Fran under a statue of Bill Clinton

What was the first large statue we saw in Pristina? None other than President Bill Clinton, in appreciation of his part in securing their independence. Of course, the sculptor was apparently trained in a Soviet art school, because Mr. Clinton definitely looks like a Russian. Still, it’s a nice tribute for Americans to see.

90% of the people of Kosovo are ethnic Albanians who practice a very moderate form of Islam. For example, we were there during Ramadan, the Islamic holy month when Moslems are supposed to neither eat nor drink from sunrise to sunset. Yet the cafes were full during the day!

The Moslem religion was introduced over the 500 years of Ottoman Turkish rule of the area. The other 10% of the people are mostly Serbian Orthodox, although there were many more when Kosovo was still a province of Serbia. Many Serbians regard Kosovo as their historical heartland. This cultural and religious attachment, along with the significant number of Serbs who live there, and large coal and mineral reserves, explains why Serbia continues to oppose Kosovo’s independence. Indeed, the border between the two countries is still very restricted.

We had a brief guided tour of Pristina the afternoon we got there: the 15th century Imperial Mosque, the 19th century clock tower, the Parliament building, a small ethnographic museum, and the Skanderbeg Monument, dedicated to Albania’s hero (we’re not sure if he still rates higher than Bill Clinton). There has been a massive amount of new construction in the last few years, along with a big increase in population.

Then we returned to our very nice Swiss Diamond Hotel, and were soon picked up by Rand Engel. Raised Jewish in Omaha, successful in business elsewhere, Rand Engel decided in 1999 that he wanted to volunteer his time and energy to helping people. He heard about a non-profit organization called Balkan Sunflower, contacted them, and soon found himself on the way to Albania to work in refugee camps serving the almost one million Kosovar Albanians who fled Kosovo in the 1999 war. 15 years later, Rand continues his good work in Pristina, primarily helping Roma and other minorities with schooling, health, and other essentials. Quiet and unassuming, Rand exemplifies what thousands of people from developed nations do in helping improve the lives of millions of others in less-developed countries.

Rand picked us up and drove us to see some other sights. First we went outside Pristina to a Serbian town to visit an 800 year old Serbian Orthodox monastery that’s still in use. Another highlight was a stop at the old Jewish cemetery on a hilltop overlooking Pristina. There was a large metal fence with a Star of David on the gate. Inside are about 100 old Sephardic gravestone slabs, mostly laying on the ground, but not seriously vandalized.

Old Jewish Gravestone

Jews started coming to the area late in the 15th century and all through the 16th after Spain and Portugal gave the Jews the choice of conversion to Catholicism, exile, or death. Thousands left, heading for Holland, the Americas, Morocco, Italy, or even further east, like the Balkans. Sultan Bayezid II welcomed the Jews into that part of the Ottoman Empire, where they became traders of salt and other goods.

There were never a lot of Jews in Kosovo. A census in 1921 recorded less than 500 in the province. During WWII they were protected by the Italians and Albanians, but after Italy was defeated and Germany took over the area, half were sent to concentration camps. After the war, over half the surviving Jews in Yugoslavia emigrated to Israel. During the Kosovar War of Independence, the Jews in Pristina, who pretty much identified with the Serbians, fled to Serbia. About 50 Albanian-speaking Jews still live in Prizren, another city of Kosovo. They are poor, and have been aided by the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee. Israel sent humanitarian aid during and after the 1998-99 war. However, Israel has not given diplomatic recognition to Kosovo. It has been described as a “delicate situation” by Israeli diplomats. The bottom-line may be that Israel has significant trade and other relationships with Serbia, and may not want to jeopardize them.

Rand Engel told me there is at least one more Jew in Kosovo, and he took us to see him. A tall man named Ilir, he runs a very good restaurant called “Renaissance 2”. To find it, you walk along Geo. Bush Bulevar (I’m not sure whether the street is named after Bush I or II) till you pass the “Green Pharmacy”, then go down the adjacent alleyway 100 feet till you come to a building with two big wooden doors. There are no signs on the street, nor even on the building itself, but this is the “Renaissance 2”. Once inside, Ilir greeted Rand warmly, and seated us at a big wooden table. We were quickly served two pitchers of alcoholic beverages: one of local red wine, the other of raki, a local variation of slivovitz. Both were very drinkable, although we were wisely moderate in consumption.

Ilir came and chatted, using “Shalom” plus some broken English. He confirmed that as far as he knew, he was the only Jew is Pristina. Rand told us that whenever any UN or NGO execs, or other prominent people, want a great meal, they find Ilir’s place.

Next a basket of assorted breads appeared, then a large salad bowl of fresh tomatoes, cukes, etc., then 7 plates of different appetizers: hummus, eggplant, olives, and some others we didn’t know, but all really tasty. Finally, big platters filled with grilled chicken and veal. There’s no oven or stove in the restaurant, the meat is all charcoal grilled. Finally, a delectable dessert: Crenshaw-type melon covered with a sauce made of crushed local berries. There’s no choice, it all just appears on your table, but it was all delicious. We’re not sure why it’s called “Renaissance 2”, but it was a great meal. Walking out up the dark alley was a little tricky, but we made it back to Geo. Bush Bulevar, and then Rand drove us back to our hotel.

The next day we drove 11 ½ hours from Pristina among the beautiful mountains of Kosovo, across the Albanian countryside, through the byways of the spectacular beaches and hills of Montenegro, finally crossing the border into Bosnia and Herzogovinia and the city of Mostar. But more about that later. It would have been more direct to drive through Serbia, but, as you now know, that’s not possible.