Djibouti and Eritrea (2018)

Congo (2018)

January 1, 2018

Liberia and Sierra Leone (2018 – 2019)

January 1, 2019Our Visits to Djibouti and Eritrea

Where Are They? What’s to Do? Dinner with the “Ambassador”; And 1 Jew = 1 Synagogue? (2018)

By Rich Juro

Part I – Djibouti – Fun to Pronounce, But What Else?

Djibouti is a tiny country (smaller than Massachusetts!) located in the Horn of East Africa across the southern entrance to the Red Sea from Yemen. Its neighbors are Ethiopia to the west, Eritrea to the north, and (scary) Somalia to the south.

Why go there? Fran and I have about 15 countries in the world (out of 195 or so) to visit, and Djibouti is accessible and safe. Because of its strategic location near the Suez Canal and Somalia, there are four, count ‘em, four, foreign military bases in Djibouti: France, Japan, the first foreign military base for China, and the only permanent military base in Africa for the USA. America pays $60 million yearly to Djibouti as rent, and the other countries pay significant sums too. Not bad for a country of less than one million people with little else to produce income. Tourism is another source of revenue, but these “tourists” are family or government officials of the four nations’ military stationed there.

Djibouti is my favorite place to slowly pronounce: “Did ‘ja booty?” Try it yourself. The capital city is also named Djibouti, so try saying the name twice. Its also very expensive, not because of the name but probably because of all the foreign bases and the big port. The locals that work there are paid well, but most of the rest of the urban dwellers are unemployed. So the per capita income is about $3,000 per year, which is not bad for Africa but certainly pretty basic.

We stayed at the Kempinski Palace, the only luxury hotel in Djibouti, and they knew it. The room was very nice, and very expensive. When we asked on the website about an airport pickup, first they said $125 for the shuttle bus, then “by mistake” quoted us $50 for a vehicle pickup; and that was for an easy 15 minute ride!

The city of Djibouti has almost 500,000 people, about half of the total country’s population. There are still many nomadic tribes in the countryside, living on the grasslands and shrubland raising livestock. Almost all of the people are Islamic, and that’s the official religion, but there is supposedly freedom to practice any religion. Years ago there were some Jews living there, but they all left for Israel or Europe.

There are three official languages: Somali, Arabic, and French. In the 19th Century, France made a deal with the local sultans and declared the area to be French Somaliland. 100 or so years later, in 1977, the people voted for independence from France, and it was granted. Unfortunately, there is a one-party system that has ruled since independence, so personal freedom and civil liberties are very limited. It is very stable politically, which is another reason the foreign bases are encamped there.

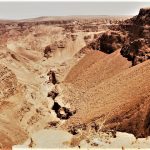

We tried to hire a guide on the Internet before we went, but there were none listed. Instead, we hired a driver and guide from the hotel’s concierge, Saleh Muhammed. They were expensive but fine. There is not much to see in the city, so we drove out in the countryside on a good paved road. First, we stopped at Djibouti’s Grand Canyon, a natural phenomenon that is impressive if not equal to Arizona’s. Then we drove to Lake Assal, a good sized body of water that is saltier than the Dead Sea in Israel. Unlike the Dead Sea, we didn’t try to float in it. Like the Dead Sea, it is located in a depression. Part of the Great African Rift, it is 500 feet below sea level, the lowest point in Africa, and the third lowest point in the world after the Dead Sea and Lake Galilee in Israel.

Lake Assal and its surroundings are the world’s largest salt reserve. Although the government is monitoring this national treasure, they are starting to mine the salt and export it. It’s hot work: the lake goes from a low of 93 degrees in winter to a high of 126 degrees (!) in the summer. Actually, all of the nation is hot year round with very little rain.

Later we asked our guide to drive us to the border with Somalia. Yes, they took us there, but, no, we didn’t try to enter that dangerous country. Djibouti is a totalitarian state, but its sun, safety, and stability suddenly appealed to us as a satisfactory site for these sightseers to sojourn.

Part II-Eritrea: Hard to Visit, Harder to Live

We flew from Djibouti to Asmara, the capital of Eritrea, on Ethiopian Airlines via Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. There’s no direct air service, and the 380 miles on unpaved roads would take over 16 hours. The good news is that Eritrea and Ethiopia signed a peace treaty recently after many years of conflict, so that we could fly Ethiopian Air for 5 hours rather than flying overnight through Istanbul or Dubai.

Eritrea is strategically located on the west side of the Red Sea, opposite Yemen and Saudi Arabia, just north of Djibouti . In fact, the name “Eritrea” is derived from the ancient Greek for the Red Sea. Asmara is the capital, and it’s a welcome change climatically. The city is almost 8,000 feet above sea level, so its about 70 degrees as a high all year round. Talk about great weather!

This area of Africa was probably home to the first humans. They recently found a million year old hominid who seems to be the link between homo erectus and us “modern” humans.

Unfortunately, now it’s not a great country in which to live. Italy colonized the area in 1892 and ran Eritrea along with neighboring Ethiopia. In 1942, during WW II, the Brits defeated the Italians, and took over the administration of Eritrea while giving Ethiopia its independence again under Emperor Haile Selassie. Later the United Nations said Eritrea should be self-governing; but big neighbor Ethiopia decided to annex Eritrea, mostly because it needed access to the ports on the Red Sea. Naturally, the Eritreans took that badly, and began a war that lasted for 30 years. It finally got its independence recognized in 1993. Of course, the war continued on or off until a peace treaty was recently signed in July, 2018.

Eritrea has been ruled by the same President since its independence 25 years ago. Its a one-party state, and there have never been legislative elections. Its among the worst nations for human rights and trails only North Korea in freedom of the press. For example, there are no privately owned news media. The long-running war was an excuse for a very nasty military conscription that has continued to this day. “Soldiers” are forced to join for below-subsistence pay for unlimited terms, and are often used to work in government mines and farms under terrible conditions. Most of the rest of the people live in poverty as well as lack of freedom. Hence, 500,000 of the Eritrean population of 5 million have become refugees, seeking asylum in Europe, Israel, North America, and neighboring countries. Even most members of the national football (soccer) team defect annually.

Here are some of the good things about Eritrea:

- Elementary school is required for all, even nomads (but I’m not sure all attend);

- School is taught in nine different languages in different regions (there is no official language);

- Some Eritreans speak Italian, from the old colonial days, but all kids now learn English, and high school is taught in English;

- Women make up 30% of the country’s combat forces, although they probably are subject to some sexual harassment;

- The government banned female genital mutilation, although that’s been hard to enforce;

- There are women judges;

- Asmara is one of the safest cities in the world;

- The life expectancy has gone from age 40 to age 65;

- A dozen years ago, the government announced it would protect the environment for 2000 miles of coastline and islands;

There are four recognized religions in Eritrea: Orthodox (Coptic) Christian, Roman Catholic, Sunni Islam, and Lutheran. Most others, especially Jehovah’s Witnesses, are persecuted. There were several hundred Jews years ago, but most left for Israel or Europe. There is one very nice synagogue left, maintained by Sami Cohen, the one resident Jew. We had a long chat with him, which you will read about later in this memoir.

Asmara, the capital, was declared a UNESCO World Heritage City last year. In the 1930’s, when under Italian rule, most of the buildings were designed in an Art Deco manner. They haven’t changed, so when you drive around Asmara, there’s not much traffic, and you can look at the colorful and unique style of architecture.

I had made arrangements for a private guide on the Internet. Sure enough, Philemon Kesete showed up at the airport and only charged us $15 for the ride to the hotel (in contrast to the $50 “mistaken low price” that we paid in Djibouti). The Asmara Palace Hotel is not a palace, but it was fine.

The next day we stopped for coffee with Philemon in an old art-deco movie theater where the lobby has been transformed into a coffee/tea house. In the shop, there were dozens of men, and a few women, sipping their coffee and socializing. Philemon seemed to know them all and introduced us to many. We had a good time chatting with the locals (but we avoided local politics). The theater will also show classic movies and European soccer games at night.

Later, we walked into a small park where a lady maintains a stand under a tree and prepares coffee in a traditional ritual. Ethiopia and Eritrea claim to be the origin of coffee, and that ritual is honored by locals and visitors alike. The coffee lady takes about 20 minutes to roast the coffee beans in a small kettle, then prepares it according to a special rite. The coffee is slowly poured into small handleless cups, accompanied by nuts or another snack. It was delicious, but we chose to leave before the traditional three cups were served. Starbucks, eat your heart out.

Recycling is also practiced. There is a big area where small shops transform scrap metal into pots, pans, and other useful implements. Philemon asked us if we wished to go to a “tank graveyard”. Sure enough, he took us to a big “outside museum” where hundreds of tanks, trucks, vehicles, and other disabled rusting hulks left from the years of war are piled on each other. I was surprised they didn’t recycle them into eating utensils. No, wait, the Eritreans eat most meals with their fingers.

Part III – Dinner with the Chief of Mission

Natalie Brown is a tall, friendly, well-spoken lady, born and raised in Omaha. She graduated from Georgetown University, and has spent her career as a foreign service officer in the US State Department. She is currently the US Charge d’ Affaires (Chief of Mission) in Eritrea. Several years ago the US protested the lack of human rights in Eritrea. In return, Eritrea made the US close its military base in Eritrea. Because of these past disputes, the Eritrean President doesn’t “receive” (grant credentials) to the US envoy. If he did, Ms. Brown probably would be the US Ambassador. I don’t know if it helps diplomatic relations with Eritrea that our chief of mission is African-American.

About a year ago, Natalie came to speak to a Breadbreakers lunch group I often attend. I couldn’t go, but Fran went, got Natalie’s contact info, and let her know we would be visiting Asmara. Eritrea has so few visitors that Natalie probably thought Fran was confused (we were her first tourists in two years!). However, we did exchange e-mails, and set up to meet her and an associate from the US consulate for dinner at an Asmara restaurant.

Eritrean cuisine is a mixture of local tradition and Italian food. The natives eat with their fingers, putting the meat or veggies into injera, a spongy flatbread. Its kind of like eating burritos with a much thicker wrap. The Italian influence was added when Eritrea was an Italian colony. So the combo is generally pretty tasty. We enjoyed excellent grilled fish, pasta, and pizza too.

No, Natalie didn’t reveal any diplomatic secrets to us. But she talked about her life as a peripatetic US foreign service officer, and we compared notes about some of the stranger places we all had been. The recent treaty between Eritrea and Ethiopia was a wonderful pact, and there were good results already. For example, Ethiopian traders were now setting up in an Asmara outdoor market, and food and other products were both more available and much cheaper with the borders open.

Part IV: One Synagogue with One Jew

“When the Spanish Jews were expelled in 1492, they went all over: Palestine, Istanbul, Iraq, India, even Yemen,” so told us Sami Cohen, the only Jew left in Eritrea. “Most of the Eritrean Jews came from Aden in Yemen, and were businessmen and traders. They are not related to the thousands of Beta Israel, the Jews who lived in northern Ethiopia for many centuries. The Eritrean Jews numbered about 500 at their peak in the 1950’s. But most of them emigrated to Israel or Europe because of the Eritrean war and tough political climate. Although I have kids or sisters in Israel or Italy, I am the only Jew left here,” said Mr. Cohen. (At least he doesn’t have to argue with the Rabbi or the synagogue Board.)

Earlier we had visited the lovely synagogue. It was built about 1900. On the outside its a beautiful white structure. There were no police guarding it, unlike many places in the world (remember, Asmara is a very safe city and there’s never been any anti-Semitism). A caretaker let us in to see the well-maintained Sephardic-style house of prayer. Some of the windows are colored, almost like stained glass, with Stars of David built into the wooden frame.

Later, we went to Sami Cohen’s residence, a lovely white stone house with a garden surrounded by a solid white wall and tall thick vegetation. An old servant let us in through the locked metal gate, followed by a barking dog. Sami is in his 60’s, still takes care of the synagogue, his house, and his business of exports and imports. He visits his kids and sisters in Israel and Europe. And he’s full of stories about the Jews that were here in his country.

“Queen Elizabeth II, when she was young and visiting here,” said Sami in perfect English, “personally awarded the B.O.E. to a Jewish man in Asmara”. That’s probably the O.B.E. (Order of the British Empire), and could have been given when Eritrea was a British protectorate after WW II.

Then Sami told a story more amazing than the famous movie, “The Great Escape”. The Irgun and other Jewish insurgents trying to get Israeli independence from Britain in the 1940’s were basically considered terrorists. So the Brits rounded up several hundred and shipped them without trial (shades of a modern Guantanamo), mostly to Eritrea and some to other parts of British Africa. One of those imprisoned was the future Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir. The Jewish prisoners attempted at least 8 escapes. Sami told us that they dug two big tunnels, and all 400 prisoners escaped and successfully made it back to Palestine to fight. However, research indicates that while in 1946 there was a mass escape (54 out of 150 prisoners), almost all were recaptured. It wasn’t till 1948 that 6 Irgun prisoners tunneled out, got to the Belgian Congo, thence to Belgium, and back to Palestine. Even after Israel’s independence in May, 1948, the British didn’t want to release the prisoners to go back to Israel, but eventually they did. Whatever happened exactly, it’s still an unknown and amazing story.

Finally, we asked Sami what happens to the Asmara synagogue after him. He looked at us, raised his hands palms up, and said, “It’s up to God.” And that’s probably the future of Eritrea too.